Ask a physicist friend to consult the I Ching – an ancient Chinese divination text – and you will probably receive a look of profound disdain. If you happen to be a physicist yourself then your friend’s eyebrows may threaten to leave their forehead altogether. It seems almost a betrayal of trust: a person they affectionately considered rational is abruptly exposed as a closet magician. Can he be serious? they wonder. Next he will ask to read my horoscope! I would like to talk a little here about why this reaction, while understandable, is wrong.

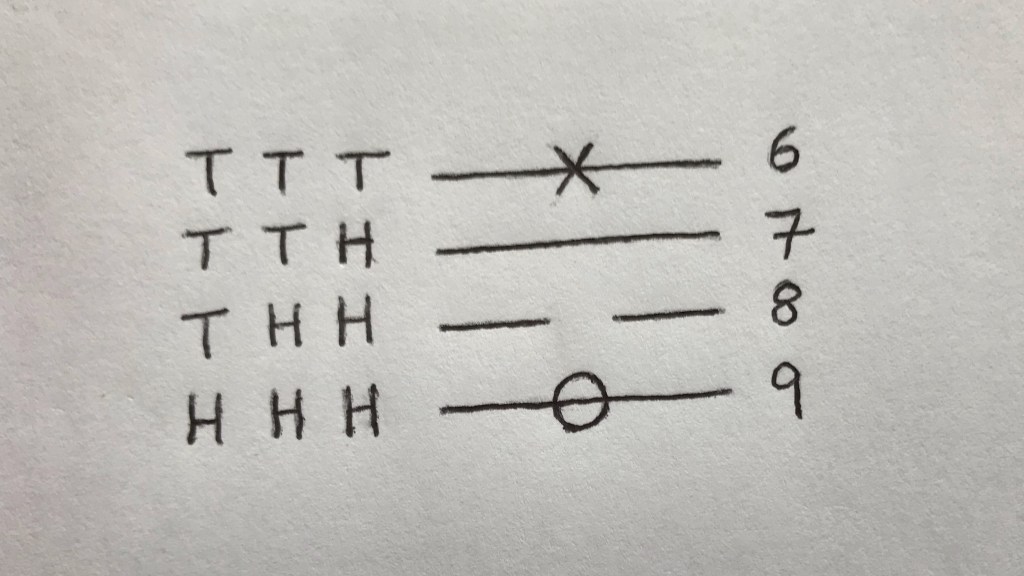

Traditionally the I Ching is said to be a “living” book because it is capable of responding, in a limited way, to any question asked of it. One begins by posing a question and the oracle’s response is given as a hexagram – an image built out of six lines arranged vertically on the page. The hexagram is found by throwing coins or separating out random bunches of yarrow stalks. I will explain the coin method here, as it is relatively simple. Tails has the value 2 and heads has the value 3, representing yin and yang respectively. Three coins are thrown at once and the number of heads and tails recorded. The sum of the three coin values corresponds to a particular type of line and the coins are tossed six times to produce a full hexagram of six lines. In Fig. 1 I have drawn a diagram of all the different coin combinations and the lines they produce. For example, two tails and one head gives 2+2+3=7, which corresponds to an unbroken line. Less likely is the result 3+3+3=9, forming the so-called old yang, represented by a circle with a line through it. The oracle contains 64 hexagrams of broken and unbroken lines – 64 possible answers – with the floating lines 6 and 9 adding texture to each prophecy.

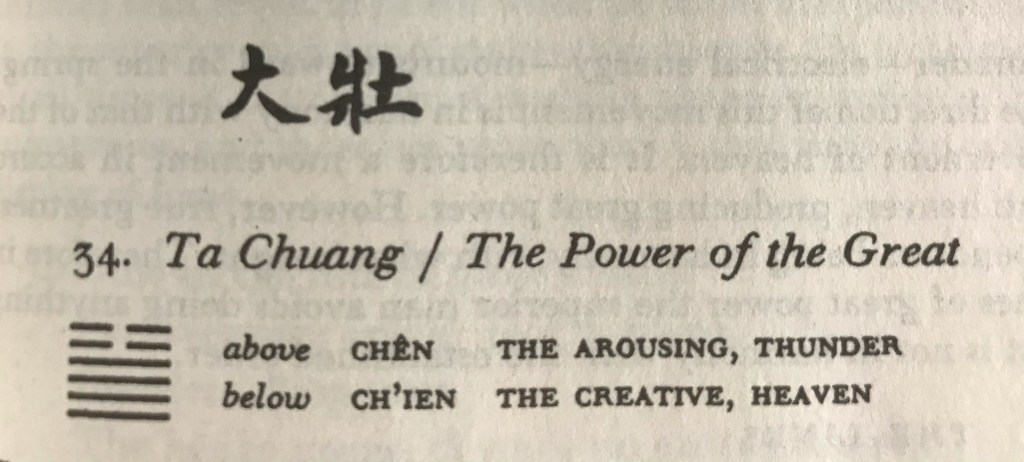

How does an abstract hexagram provide you with an answer to a question? Much of the work has been done for you by Chinese sages over millennia. Through long meditation they have tried to tease out meaning from interrelationships of form. They have dissected the hexagrams into two trigrams, or even further; they have related these components to abstract principles or concrete images, examined their relationships and proposed an interpretation. For you it remains to read the commentary on each hexagram provided by experts. The I Ching that you buy in a shop is really a collection of these commentaries. To help illustrate the process, Fig. 2 contains a picture of hexagram 34 – Ta Chuang, or The Power of the Great [1]. The Richard Wilhelm translation of the I Ching states that four solid, light lines enter the hexagram from below and are poised to ascend higher. The lower trigram represents strength and the upper movement: “..The union of movement and strength gives the meaning of THE POWER OF THE GREAT”. Thus a narrative is developed. From here, a body of broader philosophical significance has been built up over several thousand years. Your task, finally, is to read these commentaries and decide how they apply to the situation at hand.

Educated Westerners will often dismiss the I Ching as useless because they think you have to believe in magic to derive any benefit from it. According to tradition, the tossing of three coins or separating bunches of yarrow stalks is connected, in that moment, with your state of consciousness and all the aspects of the Universe at the time. The oracle’s answer therefore grows naturally out of the soil of the instant. As Douglas Adams’ character Dirk Gently would say, the value of the I Ching hinges on the “fundamental interconnectedness of all things”. While it is true that all things are connected, so to speak, in space and time, this has no influence on the quality of the oracle’s predictions. Statistical laws dictate that replacing this molecule of gas with another that is moving in a slightly different way will have no impact on the macroscopic properties of the gas (e.g. its temperature or pressure). In a similar way, although a coin toss is “rooted in the moment” [2], the present and future state of the universe cannot be meaningfully imprinted in the outcome. Unlike the old sages, I think the procedure of generating the hexagrams is random and I certainly don’t believe the hexagrams are convoked by “spiritual agencies” [3] residing in the book.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that meaningful answers are the rule rather than the exception when consulting the I Ching. How can this be, if the book operates on chance? The reason, of course, is that a human agent must apply the commentary provided in the I Ching to their own problem. Sometimes the interpretation seems straightforward, while at other times it is more obscure. Ultimately though it is the process of interpretation that is useful: you are asked to look at your problem from a fresh vantage, illuminated by the form of the hexagram. The human mind is able to interpret the symbolic meaning of things – the denotation of the letter “a”, an equals sign, a musical note – but the relationship between meaning and image is bilateral. Sometimes this two-way relationship can lead to nonsense interpretations, like when people pointed to the rubble of the World Trade Centre in 2001, observing that a cross-beam of two steel girders had survived in the form a crucifix. For some this was seen as a message from God instead of a statistically probable arrangement of two girders that had been bolted together. In other contexts, drawing meaning from images can lead to extraordinary revelations. A famous example is provided by August Kekulé, who had been working on the structure of benzene around the middle of the 19th Century. Speaking at a conference about how he made his discovery, Kekulé said he had dreamed of a snake biting its own tail and awoke with the realization that benzene must be ring-shaped!

It may be that a constant, subconscious reinterpretation of our surroundings is at the root of inspiration itself. Imagine that you have a difficult problem and decide to go for a long walk, perhaps for many weeks. There are some obvious benefits that anyone can identify: walking long distances hauls you out of your daily context, introduces you to physical hardship, deprives you of mass media culture (provided you do not spend the whole time connected to your phone) and hopefully grants you some perspective on your problems. There is another important advantage, which in truth can occur anywhere, at anytime, but which is particularly fruitful when one is walking out in the wilderness. Points in the landscape give rise to new thoughts because their appearance suggests things to the subconscious mind. The brain appears to work associatively and new discoveries hinge on our ability to combine old concepts in new ways. The landscape therefore offers up unlooked-for solutions, similar to the way the I Ching can help to recast problems and guide you towards a decision. There is no doubt that the major advantages of going on a long journey involve distancing yourself physically and mentally from normal life, but I wonder if there is this other aspect too: an unconscious unravelling of signs that can be a source of inspiration.

The I Ching can also have a more direct influence on creativity. Ursula K. LeGuin makes reference to the oracle several times in The Left Hand of Darkness [4] and Philip K. Dick famously used it to help write his novel The Man in the High Castle [5]. Dick’s story is an alternative history of the world, where the Axis powers won the Second World War and America has been partitioned into the Japanese-ruled Pacific States and German-controlled States on the Atlantic coast. The I Ching even appears directly in the text: all the major characters consult the oracle and Taoism is presented as an enlightened counterpoint to the fascist ideology of the Nazis. At several points Dick allows us into the mind of his character Nobusuke Tagomi, head of the Japanese Trade Mission in San Francisco. A particularly interesting passage comes towards the end of the book, when Tagomi is sitting on a park bench and looking at a piece of American jewellery he has just purchased. Tagomi has killed a man in self-defense and the action has shaken him. Finding no answers in the oracle, he has come across this jewellery made by one of the book’s other characters. A believer in the interconnectedness of things, Tagomi hopes the object holds the key to his situation [5]:

“He held the squiggle of silver. Reflection of the midday sun like boxtop cereal trinket, sent-away acquired Jack Armstrong magnifying mirror. Or – he gazed down into it. Om, as the Brahmins say. Shrunk spot in which all is captured. Both, at least in hint. The size, the shape.”

Tagomi perseveres:

“Metal is from the earth, he thought as he scrutinized. From below: that land which is lowest, the most dense… The daemonic world of the immutable; the time-that-was.

“And yet, in the sunlight, the silver triangle glittered. It reflected light. Fire, Mr Tagomi thought. Not dank or dark object at all. Not heavy, weary, but pulsing with life… Which are you? he asked the silver squiggle. Dark dead yin or brilliant living yang? In his palm the silver squiggle danced and blinded him…”

Here we are granted a glimpse of the Taoist perspective. Some of the advantages and limitations of this way of thinking are exposed. Using the I Ching can excite a new aesthetic appreciation of the world, a fascination with the most nondescript objects, a re-evaluation of their significance. The oracle is more than two thousand years old, but younger than the mind of modern man. People can still use the wisdom contained in the I Ching to help them work through their problems. Eventually, perhaps, it may tell us interesting things about human psychology and creativity.

References and Further Reading

[1] R. Wilhelm and C. F. Baynes and C. G. Jung, The I Ching; Or, Book of Changes: The Richard Wilhelm Translation Rendered Into English, Third Edition. Penguin Books, 2003.

[2] P. K. Dick and E. Brown, The Man in the High Castle. Penguin Classics, pp. 19, 2001.

[3] R. Wilhelm and C. F. Baynes and C. G. Jung, The I Ching; Or, Book of Changes: The Richard Wilhelm Translation Rendered Into English, Third Edition. Penguin Books, pp. xxv, 2003.

[4] U. K. LeGuin and C. Miéville, The Left Hand of Darkness, Gollancz, pp. 60, 2017.

[5] P. K. Dick and E. Brown, The Man in the High Castle. Penguin Classics, pp. 218-221, 2001.