Dialectic for Four Physicists

This post was written after speaking to a number of professional physicists who now use ChatGPT to complete certain language-based tasks. First, an excerpt (not-too-faithfully reproduced) from one of our conversations:

X: “Haha! Christ… Now Z is starting to understand why I hate Grammarly…”

Y: “Why do you hate Grammarly?”

X: “Because it infantilises us. You just need to learn how to spell, how to construct a sentence… The adverts are ridiculous: they ‘interview’ people who have English as their first language – whose job it is to draft emails or write reports – and these people gush about how Grammarly corrects their spelling and completely re-structures their syntax. They should be ashamed…!”

Y: “I use it all the time. Otherwise I can read the same sentence ten times and it still doesn’t make any sense.”

X: “It’s probably better to use Word, which just corrects spelling and prompts you when you’ve made a grammar error with a blue line.”

Y: “I think it’s fine as long as you’re just using it to check what you’ve written.”

X: “Yeah, but the effort of trying to compose the text yourself is useful. It is exactly the same principle as when you were writing your PhD thesis: the thesis has no intrinsic value as a book in itself – nobody reads it except maybe two or three beleaguered doctoral students. The entire purpose of writing it was to help you pass your viva. The thesis is designed to shape your mind, to streamline your ideas in preparation for the final oral exam. Writing the theory section forced me to confront important details I had succeeded in glossing over for three years…”

Z: “I would rather do science than spend all my time writing about it. I used ChatGPT to write an abstract for [insert conference acronym here] last week. I just gave it a list of all the things I wanted to say, it wrote the text, then I checked it and sent it off.”

X: “God… But if you use ChatGPT to draft things all the time you will start to lose the ability to do it yourself! Writing an abstract gives you an opportunity to reflect on what you’ve achieved and its real impact. Sure, you can probably travel a little way with just the bullet points, but building syntax is important. It’s part of how we think. They say that the best coders are those who grew up with computers because they practically had to build the computers themselves, they were involved in all the fundamental stages of its development, the hardware, early internet…”

Z: “You don’t have any evidence for this!”

X: “Of course I don’t have any statistics or convenient examples. No one has studied this stuff. But there’s lots of evidence for losing skills if you neglect them. My handwriting is terrible because I have spent the last few years coding and drafting most of my writing on a computer. And if I used ChatGPT to generate all of my French emails then in a couple of months I wouldn’t be able to write them properly. I would lose part of my vocabulary.”

Z: “True. But you actually want to learn French…”

X: “It doesn’t matter whether I want to do it or not – it’s a clear example of how our skills atrophy without practice. And even if you don’t like writing it is still an essential skill. There are plenty of people you meet who will say ‘I have no interest in maths’, or ‘I have no interest in politics’, but these things are still important to understand. It’s why we educate our children. They need to be able to think critically if they are going to be free, which means they need to learn how to read properly and do basic calculations even if it bores them.”

Z: “Yes, that’s true, but obviously I wouldn’t allow children to use ChatGPT. They would have to write their own essays until they become adults.”

X: “You are an adult – in fact I am speaking to three adults with physics PhDs – so you are in the highest echelon of educated people in the world and yet you are using an AI to write English for you and even little bits of code. I don’t think there is an age at which we become immune to the seductions of technology. Maturity helps, but we are surrounded by people in thrall to their mobile phones. Just having the option is often too much temptation. I use Google to get instantaneous translations when perhaps I should just sit and think for a few more minutes. And in ten years, when society is collapsing and the owls are dropping from their perches, I think we will look back and shake our heads at how people could have been foolish enough to rely on computers to do everything for them.”

Z: “Now you’re straw-manning me – who says society is going to collapse!?”

X: “I’m not. And anyway, it is collapsing now…! The climate is literally in free-fall and our society will suffer if people lose more of their fundamental skills to computers.”

Z: “AI could help us with these things. ChatGPT is a super-powerful way to make sense out of huge amounts of information.”

X: “Yeah, that’s true. Obviously ChatGPT is a formidable tool. Maybe it could help us solve some huge problems, but people shouldn’t be able to use it for trifling things that they should be doing themselves. It’s not to say I don’t see the difficulty here: it won’t work to say that only certain people are allowed to have access to ChatGPT. It’s a question of education. I expect there are also a multitude of inane and thankless jobs that can and should be automated – even if these jobs have probably grown out of prior technological revolutions. Perhaps there are some problems that can only be tackled with an AI, but really the fraction of the human population dealing with this type of complex problem is very small.”

Z: “I still don’t want to waste all my time writing abstracts for conferences! I am more efficient as a scientist if I use ChatGPT to do the boring stuff that I am not interested in doing.”

V: “And before computers we had to do all our integrals by hand…”

X: “Efficiency is rarely a good justification for anything. At least, not in the way it is usually defined. It’s like when we choose between a lawn mower and a scythe to cut the grass. Everyone uses a lawn mower because it is more “efficient”, but it is hideously noisy, violent and composed of hundreds of components made from exotic materials. A scythe is often much better: it requires a human to do physical exercise to wield it, there is a technique to learn… Even the fact that it takes longer can be beneficial if it allows you time to think, to escape into quietude. It may seem more efficient to let ChatGPT write your abstracts, but it is actually robbing you of time spent on a useful activity.”

“As for the integrals, it’s much better when you know how to do them. At work, the head of my lab is practically the only person who still can and it is incredibly useful to have a feeling for what they mean.”

V: “But X, you told me the head of your lab is a maths genius…”

X: “He is! But the integrals aren’t all that difficult in themselves – not all of them, anyway. You’re right that there are moments when it is preferable – even necessary – to reach for your computer, but we do it too much. There is a middle path, where we think carefully about when we should be using them. It shouldn’t be a reflex. Going back to efficiency, look at Dyson’s much-vaunted hand-driers: when I was last at Amsterdam Schiphol I saw a little girl in pigtails walk out of the toilets with her eyes screwed shut and her hands clamped over her ears! It was perfect crystalline proof of how abysmal the design of these machines is, even if they dry your hands in ten seconds and everyone considers them marvellously efficient…”

The Great Leveller

On further reflection, having spoken to a data scientist friend who has started to use ChatGPT to help him draft code:

Using ChatGPT to write code risks catapulting you out of your intellectual depth, making it harder for you to personally progress even if you appear, superficially, to be completing assignments. This means you become increasingly reliant on the AI for a creative solution and may begin to feel bored – even redundant. The practice develops at first because it means that people with little real experience or training can quickly start to do work that would ordinarily be beyond them. In the short-term this seems valuable, but eventually it prevents people from developing the deeper understanding required for real innovation. Later, it will probably lead to a rapid turnover of disillusioned workers that employers will (erroneously) cite as evidence that ChatGPT is needed to maintain productivity in a fast-flowing and capricious labour landscape.

I have seen this effect in universities, where students naturally want to “succeed” and feel pressured to get the best grades possible to distinguish themselves from their legions of peers. These students quickly resort to the Google search engine rather than accept that they do not really understand and should appeal to a professor for guidance or simply accept a lower grade. Then as they rely more on the internet for “prompts” and the course content gets more difficult, they lose confidence and become reliant on it. There is genuinely only a vanishingly small percentage of students who are immune to this effect and they are only immune because they are brilliant.

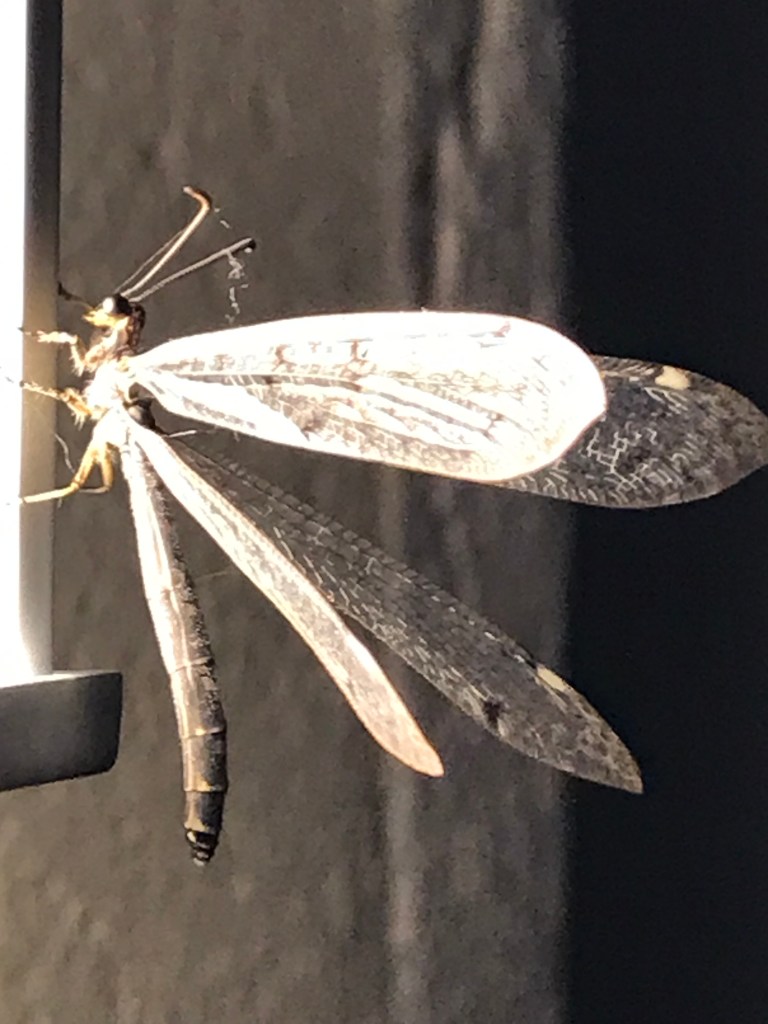

This is also why there is little point (from the point of view of improving humanity) in using an AI to produce art and why it is extraordinary that architects and so-called “creatives” are dedicating so much time to Midjourney, even if the output is frequently breathtaking. Creating art is beneficial in large part because of the effect it has on the artist. Making art is, in fact, a compulsion. It forms you, because learning and growth are non-linear feedback processes. People who become interested in Midjourney are not artists in any meaningful sense, willing as they are to exchange all the joy of craft for an outcome that they played only the most incidental part in creating. It is doubtful that half of them have more than a rudimentary understanding of how to balance, or lead the eye into, an image and Midjourney will not help them to develop these skills. So it has proved with the revolution in digital photography, which enables people with even the most impoverished technical and artistic nous to photograph a goldcrest in darkness at five hundred yards, with perfect resolution of rain-flecked feathers and claws, but without an atom of drama or sensitivity in their composition. Another triumph for democracy, whose importance cannot reasonably be denied, which produces, however, a near-endless photo-montage of no artistic value whatever.

The most spirited defense of AI technology usually comes from the highly intelligent, well-educated, affluent minority who have identified how AI can be used effectively in their own work. They do not see that they are the exception that proves the rule; they wear noise-cancelling headphones in the London metro like everyone else.