From Modern Elfland by G. K. Chesterton

+++

Human technological and military advances are locked in a perpetual striving for improvement that can never end except by mutual agreement. It comes down to a problem of trust: can you rely on your neighbour not to continue their research and either outcompete you economically or threaten you with physical attack? Military expansion is not, therefore, just caused by a few belligerent generals. It responds to a strategic problem that – in the absence of trust between parties – forces countries into a permanent state of escalation.

This question of trust appears in a whole range of leadership scenarios: in the nuclear arms race of the Cold War, in the tension between the state and the market and the coordination of an international response to climate change. All of these situations can be recast in terms of the “prisoner’s dilemma” – a thought experiment in game theory – where two rational people can cooperate for mutual gain or betray their partner for an individual reward. The cycle of hostility can only be broken through cooperation or total domination of foreign parties.

Unfortunately for the human race, many of the major threats to its existence hinge, now, on its ability to coordinate internationally. This is difficult because sympathy and understanding must bridge cultural and historical divides. Worse: technology has now reached a point where the consequences of one nation’s actions have world-spanning consequences. As Asimov observed in the twentieth century, the destruction of the Amazon rainforest by Brazil would destabilize the climate of the entire Earth.

+++

“Invisible even in a telescope magnifying sixty times, even in purest summer sky, they drifted idly above the glittering Channel water. They had no song. Their calls were harsh and ugly. But their soaring was like an endless silent singing. What else had they to do? They were sea falcons now. There was nothing to keep them to the land. Foul poison burned within them like a burrowing fuse. Their life was lonely death, and would not be renewed. All they could do was take their glory to the sky. They were the last of their race.”

J. A. Baker, Peregrine [1]

All technology relies on a localized imbalance that can be leveraged for material advantage. Consider monocultures, where large areas of land are given over to the intensive cultivation of a particular crop. In the interests of efficiency and short-term yield, the farmer replaces a mix of many species with just a single variety. This technique works, provided natural systems of renewal can continue to function outside of the area under management. Once the disturbance becomes more general, however, the existing biological system will start to break down. Success relies on the technology remaining a localised – rather than a global – disturbance. If the imbalance becomes general – if the disturbance spans the entire system – then a crisis is necessarily triggered.

The world has always been finite, but only now that human industry has surpassed a certain critical size is this reality noticeable. Like Uroborus of the Greeks or the Norse Miogarosormr [2], our appetites have grown so large that they compass the world. The biosphere is engaged in new kind of auto-ingestion, where we consume processed foods and supplements and bi-directional digital media is integrated more and more invasively into our bodies and minds. But there are other products of industry which find their way inside us accidentally: detergents, pesticides and agricultural run-off seep quietly into our rivers and seas and the kilter of gases in the atmosphere is warped by the products of combustion – not enough to affect our ability to breathe, but sufficient to alter the climate and the growth rate of trees.

+++

“We are survival machines – robot vehicles blindly programmed to preserve the selfish molecules known as genes.”

Richard Dawkins, The Selfish Gene.

Assuming that it did not just appear one day fully-formed, as an emergent property of consciousness, morality must have developed by some statistical rule of survival. Morality would therefore have grown naturally out of a process of Darwinian selection, like the rest of our bodies; and since they have an important influence on how we behave towards other animals, moral principles must mirror the mathematics of game theory, which is the mathematics of interpersonal relationships.

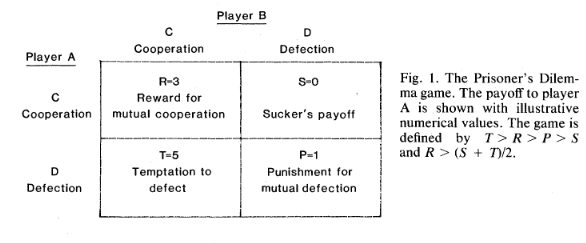

In The Evolution of Cooperation, Robert Axelrod used computer algorithms to study how morality might be naturally selected. The algorithms competed one-on-one in successive bouts of a game called the prisoner’s dilemma. In the game, two players are given the choice of cooperating with one another or defecting. The players are isolated, so their decision can’t be affected by knowledge of the other’s choice. If both players cooperate then they will receive a reward and if both defect they will be punished, but if one defects and the other cooperates then the defector will receive a more significant reward than if both parties had cooperated. So there is a temptation to defect if your opponent cooperates, but a punishment is incurred if both parties defect. Axelrod’s rules of quantitative reward and punishment can be seen in the “pay-off matrix” below [3]:

Each of Axelrod’s algorithms were programmed with different moral principles – different relationship strategies – which determined to what extent they would cooperate or defect. Two algorithms would play the game a set number of times and their cumulative scores would be recorded before a winner was declared. Algorithms would also be able to make decisions based on the outcome of previous encounters. For example, they might be programmed to defect if their opponent defected in the previous round. Remarkably, Axelrod found that the algorithms which were most successful in large tournaments (where each algorithm would play against many other algorithms over a long period of time) tended to possess the following four characteristics [4]:

(i) They would be “nice”, which means they would tend to cooperate and never be the first to defect.

(ii) They would be reciprocal, or retaliatory. They would return defection for defection, or cooperation for cooperation.

(iii) They would not be “envious”. They would try to maximize their own score, rather than try to keep their score higher than their competitor’s.

(iv) They would not be too obscure or scheming in their approach. They would have clarity of strategy to encourage cooperation.

In effect, he found that “altruistic” strategies were more successful than “greedy” strategies.

Axelrod’s experiments were simplified zero-sum scenarios1, but we already have evidence that cooperation is a more effective social survival strategy than selfishness, because humans are cooperative and other social animals are too. Chimps, gorillas, whales and various birds exhibit emotional behaviours that closely mirror our own. They appear to be capable of experiencing emotions like grief and love; they have their own social hierarchy and sometimes can even recognize the social hierarchies of humans. What we are finding, then, is that our emotions and even our morality grow naturally out of physical and mathematical laws rather than automatically from the spark of human consciousness itself – they develop in animals with strong social relationships because survival in groups promotes a certain type of behaviour.

+++

Technological progress is much easier to define than progress for humanity as a whole. Where technological innovations enhance the speed, scope, power or efficiency of a machine, their benefit to humanity can only be assessed subjectively, according to context. Often it is difficult to say whether a given technology represents a genuine step forward because (i) its implications must be determined for many people in diverse scenarios before you can say with any certainty what its impact will be on humanity as a whole, and (ii) certain of our human needs are in conflict with one another, which means a technology that is valuable in one scenario may be useless or even damaging in another.

Using a machine to reduce your burden of work isn’t automatically a good thing. Though kitchen appliances and washing machines have saved many of us from lives of crushing drudgery, it is also clear that humans aren’t built for leisure alone. Too much free time breeds neurosis and the experience of genuine hardship – physical or mental – is the source of many human capacities we admire. In The Road to Wigan Pier, Orwell writes [5]:

“The truth is that many of the qualities that we admire in human beings can only function in opposition to some kind of disaster, pain, or difficulty; but the tendency of mechanical progress is to eliminate disaster, pain and difficulty. In books like The Dream and Men Like Gods, it is assumed that such qualities as strength, courage, generosity etc., will be kept alive because they are comely qualities and necessary attributes of a full human being. Presumably, for instance, the inhabitants of Utopia would create artificial dangers in order to exercise their courage, and do dumb-bell exercises to harden muscles which they would never be obliged to use. And here you observe the huge contradiction which is usually present in the idea of progress. The tendency of mechanical work is to make your environment safe and soft; and yet you are striving to keep yourself brave and hard.”

Now that many of us do live in technological Utopias where material difficulties are slight, we find that there is a peculiar loss of meaning in our lives. Dangers must be manufactured; we consume increasingly violent and exaggerated forms of passive entertainment; and instead of using our muscles for work, we exercise to look good, or simply because it is healthy – even though we know it is less spiritually nourishing than constructive work. All this in a society that has seen decades of technological “progress”.

Thus the debate about human progress continues, with one side citing huge improvements in the security of ordinary people, and the other a decline in quality of life brought about by these same changes. We have academics like Steven Pinker who undertake large-scale quantitative assessments of human wellbeing and conclude that we have never had it so good. Then there are thinkers like Havel and McGilchrist who contend that – despite the huge material advances we have seen in recent decades – there is something deeply unsatisfying at the heart of our 21st Century techno-bureaucratic utopias.

It seems that once the basic requisites of human survival have been fulfilled, it becomes more difficult to say whether new technologies are truly useful. It isn’t even possible to say in what way a new technology will change us. What is the value of a light that is activated by voice? Is it the same for a member of the public or for workers from a specialist field? Common sense suggests not. What is the value of a machine that thinks for you, eats for you and moves for you? Again, common sense is required to identify the type of scenario where the technology might be applied advantageously. Often the question is more about who should use the technology, rather than the intrinsic value of the technology itself. If our human natures are so disposed that we cannot use a particular technology wisely, then it should not be used. The difficulty is how to establish this in advance.

Determining the benefits of a new technology to society is further complicated by human psychology. We find ourselves driven towards opposing goals like excitement and security, or work and leisure, where fulfillment of one goal conflicts with fulfillment of the other. Our brains try to resolve this paradox by employing “common sense” – a kind of implicit knowledge of where to stop – because we have impulses that are simultaneously hard-wired and ineluctably opposed.

The tension between our needs and desires is what makes the praxis of government so difficult, but it also provides fuel for the eternal battle between Luddites and technophiles. Once you have used technology to satisfy the fundamental needs of a people, your attention necessarily moves onto needs or desires further down the hierarchy of importance. And these needs – depending on the situation – may not truly be needs at all. In some cases, your satisfaction may be unnecessary or even dangerous. And identification of a desirable desire is rarely straightforward. Some things are good for you even if you do not want them, and so there is a confusion between things you “want”. On one level you want to eat the chocolate and on another level you want to be healthy, or to be the type of person who can resist temptation. Orwell felt that, as technology becomes more advanced and ubiquitous, it would be harder to reconcile these two types of desire – the desire to solve a problem mechanically and the desire to become a better person by working through it yourself [5]:

“Barring wars and unforeseen disasters, the future is envisaged as an ever more rapid march of mechanical progress; machines to save work, machines to save thought, machines to save pain, hygiene, efficiency, organisation, more hygiene, more efficiency, more organisation, more machines – until finally you land up in the by now familiar Wellsian Utopia, aptly caricatured by Huxley in Brave New World, the paradise of little fat men. Of course, in their day-dreams the little fat men are neither fat nor little; they are Men Like Gods. But why should they be? All mechanical progress is towards greater and greater efficiency; ultimately, therefore, to a world in which nothing goes wrong.”

+++

The advance of technology, while opening up new possibilities for power, also modifies the skills of human individuals. We have no objects in the modern world as beautiful as the netsuke of the Japanese, or the wine bowls of fourteenth century Syria. Skills are lost, and with them the awareness – the “sense ratio” [6] – that allowed these artworks to be produced. Though the human creative impulse cannot be killed, its expression can be stunted or changed. Digital word processing tools replaced letraset and now AI is replacing computer-aided graphic design. At every stage, there is a reformulation of technique. It is a corollary of McLuhan’s idea that different types of media alter the balance of our senses. While it is probably impossible to say whether the CAD revolution was a net gain or a net loss for humanity, it is clear that it will have changed the way designers think and see. This is the objection of the Chinese sage [7] who warned their peasant followers against the irrigation of crops by mechanical means, because they recognized that using machines begets a certain type of mechanistic thinking.

Recently I spoke to a scientist who designed several diagnostic beamlines on the Diamond synchrotron. She recalled how, at the start of her career, she was forced to learn about how every aspect of a beamline worked – all the instruments, measurement techniques, all the beamline physics – in order to build them. Now, she said, you can buy more advanced equipment directly from private companies. This is much easier and allows her students to focus on different questions – questions of science more than engineering. They use more sophisticated tools to advance a different species of knowledge.

Notes

- In Game Theory, “zero-sum” games are where, if the total benefits and total losses to each participant are added up, the sum will be zero. ↩︎

References

[1] J. A. Baker, Peregrine, p. 123

[2] J. L. Borges, The Book of Imaginary Beings, Vintage, p. 150, 2002

[3] R. Axelrod and W. D. Hamilton, The Evolution of Cooperation, Science, 211 (4489): 1390–96, (1981)

[4] Wikipedia, Prisoner’s Dilemma. URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prisoner%27s_dilemma

[5] G. Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier, Penguin Classics, pp. 179-181, 2001

[6] M. McLuhan, Understanding Media, Routledge, 2001

[7] As Ref. 6, on pp. 69-70. McLuhan quotes from Werner Heisenberg’s The Physicist’s Conception of Nature.