Potholes

Western liberal societies have fallen into an ideological hole in the road. We have been stuck in it for some time but have registered the fact only recently, because other problems have developed that are easier to measure. The pillars that underpin our high standards of living have been eroded to a point that is collectively noticeable. After decades of abundance, the food, the water, the transport networks, the postal service, medical and social care, housing, our artistic culture and social cohesion – they have all begun to turn.

At the same time, strange scenes are observed in daily life and reported in the media. At work, rules proliferate like weeds, strangling creativity in the name of safety and inclusivity. Friends can permanently incriminate themselves with a word – and an uneasy quiet reigns in many homes and public fora, where doublethink is considered essential to morality and suspected thoughtcrime is punished by “cancellation”. As record numbers of young people claim treatment for mental health issues, the atmosphere of tension and uncontrollable weirdness reaches into the theatre of politics, where flagrant charlatans are elected and re-elected to positions of high office.

If asked, many Westerners would point to Donald Trump and his supporters as the worst symptoms of our current affliction – not so I. I think the worst and most dangerous product of our times is the body of extreme, quasi-liberal ideas called “woke”. I say this not simply because it is an ugly, reductive, solipsistic philosophy that is damaging to thought, but – still more importantly – because it is the woke movement which has killed the political Centre and thrown lighter fuel on the bonfire of Populism.

Collapsing the Centre

When you find yourself in a hole, there is a tremendous temptation to hunt around for someone to blame. The Right blames the Left, the Left the Right, philosophers blame other philosophers, the woke blame the unwashed, unenlightened masses or a cabal of evil billionaires and the un-woke blame the woke or they blame immigrants. In short, we blame anyone but ourselves and then go back to our screens.

On the Left in particular, there is a tremendous hand-wringing and defeatist bemoaning of Trump. Woke liberals think the current state of politics is entirely the fault of people like him. They do not see that they are the main reason Trump was elected and then re-elected, nor that it is now their responsibility to evict him. It was the woke movement which produced an environment of debate so hostile that the only people who could survive in it were unshockable demagogues on the Right or the most vacuous, insipid species of Left-leaning politician. Ultimately, the only loud voices who could voice an opinion contrary to the woke position were politicians like Trump and Farage. And so the populist Right gained legitimacy, because it was the sole voice of common sense. Now, instead of a sympathetic discussion of trans rights, Americans are presented with a President who is completely deaf to them. And instead of having a reasoned debate about immigration in the UK, we face the prospect of a Reform government that seeks to stifle it almost completely. Essentially, the intolerance of the woke position has produced an equally extreme reaction on the opposite side of the political divide. When they killed off any high-level debate by calling their opponents racists and TERFs, woke liberals immobilized the political moderates. There was therefore no one to apply friction when the pendulum of public opinion began sliding the other way.

On the Left and Centre of UK politics we have political parties like the Greens and SNP, which were originally formed to bring major issues like climate change and Scottish national sovereignty to the forefront of the national agenda. Today, many of these parties are riven with internecine conflict, where your position on gender identity is critical to your political future. In 2019, a third of all internal motions tabled by the Green Party related to trans rights. Variation from the woke orthodoxy can be met with a “no-fault suspension” and eventual expulsion from the Green party, with more than 40 men and women having been evicted for putative “transphobia” to date1.

In many parts of the western world, we are witnessing a movement towards a more autocratic style of government. The woke cannot understand it at all, because they see it as the result of “bad actors” instead of a natural response to societal changes and their own hypocrisy and intolerance. Fascism, like any popular movement, has its origins in certain truths of human nature. The fascist dreams of a greater and nobler people who grow by experience and toughness. It is only natural for a society that prioritises safety and mediocrity to give rise to a yearning for its opposite. As votes continue to move to the Right, the average woke liberal lives in a state of perplexity, shocked by the repeated electoral success of politicians like Johnson, Trump and Farage.

Woke or Liberal?

A current of ideas has developed in the Western middle class that is markedly different from the liberal ideology that dominated at the end of the 20th century. Woke thought became obvious as a political force during recent public debates, though they developed over previous decades, culminating in a society where health and safety and political correctness have “gone mad”. The debates covered a range of topics, including:

(i) What “additional” rights and privileges – if any – should be accorded to transgender people?

(ii) Should we destroy artistic, economic and intellectual links to our colonial past?

(iii) What is a reasonable immigration policy when the UK has contributed to the collapse and impoverishment of foreign regimes?

The woke reaction to these debates came violently, like bubbles bursting at the surface of deep water. People politely advancing counterarguments, or calling for further thought before policy decisions were made, were told they were killing people, were shouted down, or were told they were as immoral as individuals on the extreme right of politics (who were just as outspoken as the woke apologists and who really did hate immigrants and transgender people). As the debates continued, woke attitudes became influential and many were integrated into the way society is run. We are now “profiting” from those changes in a culture of extreme censoriousness and “inclusivity”, where the political landscape has been hollowed out at the centre and power begins to concentrate in the wings.

My personal experience of the transition away from liberal values comes from conversations with the highly educated, scientifically-literate middle class and from working in a non-departmental public organisation. In the past five years, I have witnessed behaviour that would have been considered shocking twenty years ago. I have watched educated friends quiver with rage as they mount the most poisonous, vitriolic attacks on writers whose work they have never read and I myself have been reluctant to discuss topics in polite company for fear of being misunderstood.

When speaking about woke ideas, or “woke people”, it is vital to be clear about what we mean. The woke community is large and diverse – though almost exclusively middle class. Most of my colleagues and social acquaintances proudly consider themselves woke, so it is straightforward enough for me to outline their political views2:

On transgender people: A man is a woman if he thinks he is (and vice versa). If you do not think that a trans man is literally a man then you think trans people are lying and you are transphobic. Anyone who disagrees with, or is unsure about, the rights/privileges3 demanded by the transgender lobby is a TERF (a trans-exclusionary radical feminist). TERFs should not be spoken to or engaged with because all the necessary information about trans issues is available online and they should therefore know better. TERFs should not be allowed to speak in public spaces because it scares trans people and anything short of immediate acceptance of trans proposals is equivalent to killing trans people. Any discussion of trans rights is equivalent to the most egregious form of hate speech. Scepticism of transgender rights is precisely analogous to homophobia.

On immigration: Everyone is welcome forever, with no limits. If you would like to reduce immigration – or want to discuss changes to the existing rules – then you are a racist. Someone who wants to reduce the number of immigrants in the country is against asylum seekers. Someone who is against further immigration hates the existing immigrant communities in Britain.

On art and fashion: In art, politics is more important than aesthetics. Anything can be good art, regardless of how crapulent its execution, provided its politics are woke. You are not responsible for the psychological impact of your appearance on other people. It is not possible to dress provocatively. Comedy is only funny if it is inoffensive to woke people. The prevalence of the female form in art is an unfortunate consequence of male power that should be corrected. Ugly is beautiful.

On history and education: previous generations and cultures should be judged against woke values. These values are correct because they reflect the views of the nicest and best-educated people, living in the most rational and technologically advanced society there has ever been. White men are disqualified from talking about issues of racial equality and women’s rights because they have not directly experienced sexual or racial oppression themselves and because they continue to occupy a position of power in society. Education should be “de-colonized”. Children should be free to choose what they eat, how they dress, how to learn, how to behave, what sex they identify as, because these choices allow them to express their “true self”.

On crime and punishment: Extenuating circumstances do not exist for certain crimes. For example, all forms of rape are uniformly bad. The role of a court judge is to assess whether or not a crime has been committed – not to evaluate the harm occasioned or the degree of culpability. Laws reflect eternal truths of justice, instead of representing an ad hoc used to bridge a grey area. Imprisoning people is wrong. Celebrities should not be allowed to criticize trans issues on Twitter because they are too influential. No form of sexual attraction is “wrong”, so long as it is consensual.

On the vote: Anyone from the age of 16 upwards should be able to vote.

Frequently presented with the éclat of self-evident truisms, none of these ideas are. Most are extrapolations of liberal ideas into new contexts where they should not apply, based on a simplified conception of humanity that does not exist. If you are wondering why I haven’t included other examples of woke thought – those that might be considered more unambiguously positive – it is because these ideas were already present in the liberalism of the 20th century. What marks the woke movement out from classical liberalism are precisely those ideas listed above, eloquent as they are of the preoccupations of the contemporary bourgeoisie, with its tribalism, selective sympathy, rejection of personal responsibility and fanatical resistance to dissent or debate. John Gray uses the term “hyper-liberal” to describe these views and I will use “woke” and “hyper-liberal” interchangeably throughout this essay.

Unlike liberalism, which grew out of the community-based, grassroots activism of a working class, woke ideas were disseminated online by a bourgeoisie that is increasingly socially isolated and technocratic. Where liberal ideas were shaped over centuries, culminating in the suffrage and civil rights movements of the twentieth century and the progressive social policies of the postwar era, hyper-liberal woke ideas developed amongst the Western middle class in the early twenty-first century, steeped in a climate of postmodernism and free-market capitalism, where community feeling was weak, privatisation and consumerism were strong and people’s perceptions were increasingly shaped by what they observed on their mobile phone screens. The middle class expanded hugely in this period and it is no surprise therefore that the dominant ideology of our time is essentially a defense of middle class attitudes and living habits, where the Self is positioned at the top of the cosmic hierarchy of importance.

Transitioning to Woke

“I think there are good things about [the internet], but there are also aspects of it that concern and worry me. This is an intuitive response – I can’t prove it – but my feeling is that, since people aren’t Martians or robots, direct face-to-face contact is an extremely important part of human life. It helps develop self-understanding and the growth of a healthy personality.

“You just have a different relationship to somebody when you’re looking at them than you do when you’re punching away at a keyboard and some symbols come back. I suspect that extending that sort of abstract and remote relationship, instead of direct, personal contact, is going to have unpleasant effects on what people are like. It will diminish their humanity, I think.”

Noam Chomsky, How the World Works – p. 167.

While it is tempting to look on hyper-liberalism as a malady born of a single cause, the reality is probably more complicated. Although there have been instances where individuals have had a disproportionate impact on the direction of a country, political movements seem to grow more often from a mixing of economic and cultural factors; as the fruit of many mechanisms, interacting together and amplifying in a non-linear way. Most of the time, the best we can do is to trace the history of ideas without trying to advance any general theory about how they are developed. That said, I would like to propose two factors – one technological and the other economic/ideological – that I think have had a strong influence on the transition from liberalism to woke. I think they have done this by eroding community-feeling in Western liberal societies, while enhancing our personal autonomy/independence. Living in densely populated urban environments, without the ties brought about by shared values, traditions or religious beliefs, in a society that actively seeks to reduce face-to-face social interaction, I think we have become more asocial, our perceptions have narrowed, and we have started to develop the selective sympathy that is the ensign and hallmark of all despotic regimes.

The woke movement was born just as the digital generation (those who grew up with access to the internet) matured and began to broadcast their political views online. Our reliance on digital technology has changed the way people socialise and work; it has created megacorporations of profound influence, radically altered the composition of our high streets, changed the way people relax and the way they assimilate information. The result of this compression of the social sphere is that we have become more insular and neurotic. It is common to hear about how media algorithms and online networks have connected individuals with extreme right-wing views together – people who would ordinarily find little traction for their radical ideas. But there is no reason why the mechanism should operate only on the Right. The same process has been active on the Left for the same amount of time, contributing strongly to the growth of woke by uniting the voices of the most anxious and isolated members of our communities.

Working in concert with digital innovation, economic forces have contributed to the dominance of postmodern cultural relativism in the late 20th century. It is this nihilistic ideology – an important component of the hyper-liberal outlook – that has accentuated the social isolation brought about by technology. In the late 20th and early 21st century, “free market” economic policies were adopted in the UK with campaigns of privatisation and deregulation. This allowed companies and banks to develop as centres of political power, tying decision-making at a national level to the financial markets and weakening key public services that were previously a source of pride and trust. Other economic pressures led to geographically-concentrated immigration and the collapse/export/sale of British industries. At the same time, a “consumer culture” took hold as the middle class expanded and cheap holidays and products flooded the market. The result is a society where the middle class feel more insecure and entitled than they did before. They do not understand the motivations of others – even their immediate neighbours – who do not share their views and they look for support online, in interest groups, in identity politics, or in the oblivion of streaming services.

The liberal nihilism that developed into woke is a state of minimal artistic and political energy4:

“…You believed in things because you needed to; what you believed in had no value of its own, no function… A dog scratches where it itches. Different dogs itch in different places.”

As Gray observes, its insistence on the subjectivity of opinion renders all old values meaningless and offers nothing in return. Moreover, it has eroded the sense of community that comes from local, national or religious affiliation. When national pride is written off as jingoism, religion as mere superstition and government officials as institutionally venal and incompetent, there are few places left in which people can place their loyalty and their trust. Of those that remain, most have already been undermined by new patterns of socialising brought about by technology.

The nihilism of a modern Western liberal democracy did not allow technology to be controlled as it has been, at various times, in Asia. Since nihilism volunteers no ethical framework of its own, people have to cling to the disintegrating flotsam of their cultural traditions. With no existing ideological forces to limit the use of new technologies, these technologies were free to shape our behaviour unchallenged. Probably the most potent symbol of human behavioural change is the ubiquity of “smartphones”, which now live permanently in our pockets and by our bedsides, insinuating their way into our lives as “omni-tools” of convenience.

These technological and economic changes, the repercussions of which have built gradually over decades, have left people feeling isolated and weak. Without community, governments and big companies appear invincible – even democratically-elected governments. The sense of helplessness incurred then reinforces the importance of preserving one’s own interests. People watch the insidious decline in living standards, but do not know what to do. They are not used to acting on their own and they see no existing power structures that could help them.

I have suggested there may be a link between woke ideas and the erosion of community-feeling in Western Liberal societies. If true, we can adumbrate a chain of causation by looking for ways that communities have fragmented and face-to-face social interactions reduced in recent decades. An important task will be to examine how technology influences society in general terms. Much of the work will fall to psychologists and sociologists to probe deeper into the effects of digital tools on our way of thinking, though we can look to the work of major 20th century writers for clues. Orwell and Huxley saw that technological progress should be controlled to keep certain benefits while avoiding a mechanical utopia peopled by machine-minded technocrats. Orwell felt that this could be achieved in a modern socialist democracy, but that it was the socialists themselves who were the main obstacle to getting broad support for a socialist government. Huxley thought very seriously about how a modern utopia might be constructed, before concluding that it wouldn’t be possible in the international climate of the day. He felt that without some form of protection, countries with weak militaries would be exploited by their stronger neighbours (homo homini lupus est). McLuhan saw that the effects of these new media technologies – once generally adopted – would be far-reaching and devastating. He observed that humans have few defences against tools that change the pattern of human thought when they are used.

The Self Above All

“…But you see, it’s not me, it’s not my family

In your head, in your head, they are fighting…”

Zombie – The Cranberries.

In the closing decades of the 20th Century, when God and duty were killed and our ministers of government shown to be corrupt, man was given the “freedom” to choose his own allegiances. It was then that the Self grew to insalubrious prominence and the liberal project was superseded by a more self-centred, hyper-liberal perspective.

We see this selfishness particularly in the extremity of the hyper-liberal reaction to those who disagree with them. For the woke individual, when they say they are feeling “triggered” or “uncomfortable”, they are making a unilateral statement that justifies the extremity of their response. The statement does not consider the feelings of others – it is their own emotions that count. This is true not just in the context of the debate over trans rights. Many people today consider personal feelings to have a kind of sacred importance. They think reality conforms to what is sincerely believed. But just because a feeling is real doesn’t imply that it corresponds to something that is physically true. There are innumerable everyday scenarios where we call out other people when we deem their feelings inappropriate, where their behaviour is not commensurate with reality, or they are simply mistaken. We are all fallible. It is not unjust to say that someone is overreacting, particularly if they are known to be oversensitive or to have outstanding mental health issues. Nor is indulgence always a kindness, which should be obvious to anyone who has spent time in the company of spoiled children. Good parents don’t waste time trying to prove scientifically that a child’s response is disproportionate or that their feelings – though real enough – are unjustified. They know instantly and intuitively that the response is absurd. It is measured against our values and our knowledge of how people normally behave. Yet there are many hyper-liberals who would disagree – who believe that reality conforms to hyper-liberal opinion on topics as diverse as biology and socioeconomics.

I once went to a vernissage at the CAPC musée d’art contemporain in Bordeaux where a trans woman artist was singing. Though they identified as female, the artist was physiologically male – and I have since forgotten their name, so I will refer to them here as M-. During the performance, I remember being transported by the beauty of M-‘s voice and the music. Before “she” began, however, M- received our welcome applause and said how grateful she was, because she had just walked up the Rue Sainte-Catherine (Bordeaux’s 1.2 km-long high street) and been subjected to laughter and comments. She was, as I recall, wearing a frilled mini skirt, fishnet stockings, platform heels and a corset – all in silver or metallic bluish-purple. The crowd’s response was predictably outraged and shouts of support merged into a sympathetic ovation.

My own response to M-‘s experience was more conflicted. Certainly no one wants to be openly laughed at, or to have comments directed at them in the street. I consider it a fact of life, however, that if a man puts on a corset and heels and walks down the busiest thoroughfare of a major city then they are going to attract unwanted attention. Essentially, someone dressed in a striking and unusual – dare I say even amusing – fashion was upset by the reaction of the general public. But oddities obtrude. And pretty women have to contend with similar levels of discrimination (positive and negative) throughout their lives – short skirt or no. For the most part, they learn to bear this discrimination with admirable stoicism. They understand that there are types of discrimination which cannot be erased without the most appalling tyranny and the destruction of humans as social animals.

Personally, I don’t see M-‘s experience as evidence that transphobia is rife in Bordeaux or that trans rights should be brought to the forefront of France’s national agenda. I think rather there is a tension between M-‘s desire to be noticed – to be at the centre of a spectacle – and to be treated the same as everyone else. This tension also appears more generally within the transgender community. On the one hand there is a desire to be singled out for special awards, to have specialized support groups and constant verbal and written acknowledgement of their distinctiveness, while on the other hand they want to be seen as completely normal. If it means we have to disrupt the smooth functioning of the rest of society to chase a logical inconsistency – even down to policing what people are allowed to say and think – then it seems hyper-liberals are happy to do so.

When hyper-liberals hear about experiences like M-‘s, they are apt to conclude that not only has great harm has been done but that society is transphobic. The reality, however, is that hyper-liberals communicate with “transphobes” primarily via the internet. In their day-to-day life, they are surrounded by other middle class people who fully support the trans lobby. It is only on the very fringes of society that genuinely transphobic sentiment is found. The overwhelming majority of other people don’t care how transgender people identify so long as they can just get on with their lives as normal. The world looks very different to a hyper-liberal, however. Peering through the narrow aperture of their Twitter feed, the world seems remarkably hostile. Words and images develop a dizzying potency when they are beamed directly and repeatedly into one’s own home. Eventually everyone – everyone – becomes overly sensitive. Then on the rare occasion that someone suggests our time and money would be better spent tackling issues like the job market, or climate change, they are told in an outraged tone that “people are dying” – as though it has nothing to do with the transgender people themselves and their own insecurities.

The self-centredness of hyper-liberal opinion is likewise clear from their position on major political issues like immigration. Immigration is now sufficiently important to the British public that many consider it to be the most significant public issue – even greater than climate change or “the economy”. This is clear from the results of recent council elections, where Reform UK won the largest number of seats. Hyper-liberals, by contrast, not only do not consider it important but see any discussion of immigration laws as evidence of racism.

The tedious length and bitterness of the immigration debate comes principally from a difference of perspective. In many parts of the UK, local people see that the substance of their towns and cities is changing. They see foreigners in the streets who do not have (and shouldn’t be expected to have) British habits of living. They read that factory and farm workers come here temporarily to earn money and send it abroad, then they read about boats full of desperate migrants trying to enter the country from France or foreign investors buying up property in desirable locations. Many respond to this situation by blaming immigration laws, which they feel are too lax.

Hyper-liberals on the other hand observe no significant changes brought about by immigration – that is, no changes that they cannot easily cope with or do not benefit from themselves. They live in areas that have seen little in the way of demographic change or economic hardship. Their money insulates them from those parts of town where low-paid immigrants live beside the most deprived members of British society. Like everyone else, they live largely online, in the narrow space between their noise-cancelling headphones and computer screens. Their interaction with immigrants is therefore limited to the highly-educated individuals they meet at university (who are essentially indistinguishable from themselves, having retained little of their parent culture) or the anonymous multitude that delivers their pizza and Amazon parcels. They have read about the United Kingdom as a colonial power, with its piebald history of racist domination, and they suspect that Reform voters either don’t know this or are too unpleasant to consider it. They assert that studies have shown (i.e. eternally and conclusively) that immigration is economically beneficial. To want to discuss a new policy is seen as evidence of racism.

In fact, there is always an upper limit of immigration that a country can support. No country can withstand unbounded immigration. The reality – acknowledged by all governments – is that immigration brings benefits and challenges that must be weighed. When Western liberal countries make decisions about immigration policy their concerns are largely economic, though other countries exist – like Japan – that are more ethnically homogeneous, where the public perception of immigrants is less favourable and immigration is kept low even to the detriment of the economy5. The right attitude to immigration depends on the socioeconomic context. In the UK, it might be argued that our history of intervening in the government of other countries imposes on us a duty to welcome more immigrants than might be considered desirable or “beneficial”. But there are many other factors to take into consideration as well – ministers must balance our need for carers, laborers and agricultural workers against other factors, such as the ability of the UK’s infrastructure and welfare system to support more people.

The complexity of the immigration issue can be appreciated via simple thought experiments. Consider, for example, a society where the working class has shrunk and the inflated middle class is increasingly employed in technical and bureaucratic roles. Suppose also that the offspring of the middle class aspire to jobs in science, medicine and law that require extensive training (e.g. postgraduate degrees). In this situation, how is society to continue to function without immigrant carers, farm laborers and factory workers? We can also consider a scenario where the country has a growing population that is too large for it to support. Existing stresses on housing and public services are worsened as more people arrive in the country and high levels of immigration in certain areas (combined with an economic depression) exerts a psychological strain on local people. Perhaps there are problems in specific sectors of the economy- for example, there may not be enough training positions for postgraduate medical students, who are competing against tens of thousands of peers and international graduates for a few thousand places. How, in this situation, is the country to cope without limiting immigration?

Contemporary Britain is a sort of convolution of these two pictures, which means the solution is neither unbounded immigration nor closed borders. Many of the problems attributed to excessive immigration in the UK are economic at root. Though they are related to immigration laws, they are driven primarily by the pressure to produce cheap services and commodities. An open and ongoing discussion is needed to maintain a healthy immigration policy and, as with all political discourse, the discussion cannot be open if it is not respectful. The woke assertion that there should be no limits to immigration and the only problems related to immigration stem from the number of racists in Britain is absurd and only serves to strengthen the political influence of Reform.

It seems reasonable to me that selfishness is responsible for many of the more unpleasant woke ideas because the reaction to woke amongst many young people of the same class is equally selfish. Go to any city in the country and you will find a young middle class man who, upon seeing someone in a more unfortunate position than himself, will remark in a self-satisfied tone that the man has made his choice, that there are other jobs you can do, that people are lazy and the important thing is to make money and look after yourself. You will see that there is some truth in what he says – that society has become obsessed with easy living and quick returns and supporting everyone irrespective of merit – but you will also note the scorn in the man’s voice, his fear of illness and dirt and work. You look at his own flimsy accomplishments and suddenly you understand that beneath the glossy carapace this man is remarkably soft. You see that his success derives largely from the support of those around him, from a handful of serendipitous events, and his new philosophy has been retro-fitted so he can feel better about himself when he leaves society in a worse state than he found it. There is some truth in what he says, certainly, but his conclusions about how to act are wrong. Ultimately, he is not so different to the hyper-liberals he decries.

Neuropathology or neurodivergence?

“Somewhere or other there’s a backroom boy, his soul working in the primordial dark of a diseased yet sixty horse-power brain.”

Mervyn Peake, Titus Alone.

The concept of “neurodivergence” developed because there are degrees of mental illness and conditions of experience that are not strictly pathological. In particular, it was thought that describing autistic people as “neurodivergent” (i.e. different) instead of “disabled” or “ill” would reduce the stigma associated with their condition.

What precisely do people mean when they describe someone as neurodivergent? In a recent survey of UKRI employees, neurodivergence was defined as:

“… the understanding that people experience and interact with the world around them in many different ways – there is no one ‘right’ way to think, learn or behave.”

I think the statement reads more like a creed than the definition of a psychological condition. It feels like the author is trying to make a value judgement sound scientific. Just because you cannot write down a single “right” way to behave to cover all contingencies doesn’t mean there isn’t a right way to behave and that certain modes of behaviour aren’t wrong. You may as well say that Raynaud’s syndrome is not an illness because there is no one “right” way to pump blood into your fingers and toes. And though there may not be only one right way to think or learn, there are certainly slow ways and wrong answers.

In the same UKRI survey, people with “autism, ADHD, dyslexia, dyspraxia, Tourette’s syndrome, or mental health conditions” were described as being neurodivergent. This is striking because the list combines mild or difficult-to-diagnose conditions with serious, chronic neurological disorders. Lumping all these conditions together and asserting that they are not pathological – just “differently normal” – has the simultaneous effect of whitewashing significant behavioural conditions and making almost anyone a candidate for neurodivergence. It is another example of how, in trying to invent an imaginary world where everyone is equal, hyper-liberals are forced into a contradiction. Tourette’s syndrome is not a different way of looking at the world – it is a neurological disorder. And only a hyper-liberal could look at a seriously autistic child and say that their point of view is just as valid, just as “right” as any other. It is not clear there is any benefit to describing a depressed person as neurodivergent. Their perspective is not just different to the norm – it is pathologically and unrealistically negative.

In recent years, there has been a tremendous rise in the number of children diagnosed or self-diagnosed with conditions like ADHD, anxiety, depression and transgender dysphoria. Now, a huge proportion of students in top schools and universities (more than a fifth of students in some American universities6) are considered disabled in some way. If that proportion of students were actually disabled it would be a national crisis – it would be a problem of primary magnitude. My suspicion therefore is that there exists a kind of tacit understanding amongst parents and teachers that this isn’t the case – that most of the children diagnosed with these conditions are not really chronically or congenitally ill – but no one is brave enough to call out individuals for fear of lighting on an edge case or triggering an avalanche of retribution. When disabilities are neurological, there is a degree of ambiguity in their diagnosis that can be exploited. In the particular case of children with significant emotional or behavioural problems, a medical diagnosis provides parents with a seemingly scientific solution – a name for a condition, a drug-based or surgical treatment and extra time on their exams.

In hyper-liberal discourse, there are repeated allusions to the sanctity of one’s personal feelings – and the perception that certain feelings are unquestionable may have contributed towards an inflated diagnosis of mental health conditions. If a child says they are depressed, there is a tendency to immediately believe them and to prescribe anti-depressants; if a child cannot concentrate or cannot behave, they have ADHD; if a girl says they are a boy, then who are you to question another person’s feelings? The result is classrooms full of children with putative mental disabilities. When neurodivergence is used to classify all these different neurological conditions it feels like the final word in the impossible mission of equal status for all, allowing people to be treated as though they are disabled without being formally recognised as such.

In defence of the term “neurodivergence”, people will sometimes cite cases of individuals whose apparent mental “disabilities” are offset by prodigious talents in other areas. I can list numerous examples from my own experience, such as individuals with dyslexia that have remarkable visual and artistic skills, or autistic people with conceptual reasoning that far exceeds those of their “healthy” peers. Naturally these exceptional talents are a source of contentment and meaning. Indeed, sometimes they are seen as a cause for general celebration – there are doubtless many figures of history who would probably be classified, in the modern vernacular, as autistic or dyslexic. The fact that people can find strength and happiness in their mental disability is, however, beside the point. Maladies are identified as conditions, hors normes, because they make certain aspects of ordinary life difficult. If you find this hard to believe, ask yourself if you would actively choose to have a child with a mental or physical disability over a conventionally healthy child.

If the term “neurodivergence” has any value – and I am not entirely convinced it does – it may be useful as a catch-all term for mental health conditions where the negative symptoms are sufficiently minor that medication is not required. While calling a “highly-functioning” autistic person “neurodivergent” is probably preferable to “mentally ill”, I wonder whether we wouldn’t be better served by other phrases without the pseudo-scientific connotations. Anthony Hopkins, writing in his memoir, agrees with his wife’s assessment that he probably has Asperger’s syndrome, though he adds wryly:

“I’ve chosen to stick with what I see as a more meaningful designation: cold fish.”

Wishful Thinking

Contrary to popular belief, a STEM education doesn’t afford you supernatural powers of self-programming. Hyper-liberals are animals like any other, but they like to believe that humans are free to choose their beliefs. Any lack of conformity is stubborn and immoral because woke ideas are rational, final and self-evident. After all, does the internet not give everyone access to the necessary facts? Just like in the Fascist and Communist regimes of the 20th century, any lack of conviction – any vacillation – represents a kind of tacit collusion with the enemy that merits unflinching condemnation.

Of course, hyper-liberal invective is always levelled at people on the other side of the ideological fence. If they themselves are guilty of some slip, or even systematic malpractice, they quickly absolve themselves on grounds of mental health, stress, anxiety, or sensitivity to being “triggered”. Since they know they are ultimately on the right side, their actions are forgivable, but the working class man from down the road who wants to reduce immigration is a “bigot”.

Orwell observed in the 1930s that the attitude of the average middle class socialist was one of condescension towards their working class comrades – that they harboured a secret sense of superiority. The same might be said of the new generation of hyper-liberals who sympathize little with the working class and give no credit to their perspective.

Transgender Doublethink

Critics of woke ideas – with a few heroic and conspicuous exceptions – have scrupulously avoided the sensitive issue of transgender rights. This is understandable given the threat of public recrimination, but if you are not willing to openly explain your views then you risk being erroneously labelled “transphobic” – or worse, being unable to update your own views about the issue. The transgender debate has proved to be by far the most important factor in the freezing out of ethical enquiry and the political immobilisation of the Centre and Left. It is also the one topic that public intellectuals persistently shrink from in interview.

In the hyper-liberal view, a trans man is literally a man – they are not simply differently “gendered”. In other words, if someone who is physically and behaviourally female tells you they are a man then you must think they are man. While transgender dysphoria is clearly a real condition, in practice there are numerous different interpretations of being transgender. Eddie Izzard’s feelings about his own gender identity are quite different from those of Audrey Tang or Jan Morris, which in turn are different from those of the trans people that I know personally.

The concept of gender is distinct from sex because there are human characteristics that bridge the sexes which cannot be said to be exclusively and absolutely the provision of either sex. Speaking about gender allows you to talk in abstract terms about people – often but not exclusively homosexuals – whose appearance or behaviour diverges significantly from the sexual norm. To say that someone can “become” a member of the other sex because they feel differently gendered is, I think, to misunderstand the purpose of these two terms.

I have known “trans men” personally myself – some who have undergone medical transitioning and others who have not. While I am pleased they feel happier identifying as transgender, I do not consider them to be literally men (and neither, as far as I can see, does anybody else). Perhaps it is worth spelling out that you can have the most touching, life-affirming connection with a transgender person, where your entire mode of discourse thrills with mutual respect and admiration, without believing them to be differently sexed. If you find this hard to imagine, you probably also find it hard to imagine being able to respect someone with different political or religious views to yourself.

If you are not pragmatic about social policy you can produce serious social divisions, like those we see currently emerging in many Western countries. The reality is that there are a large number of very different people who identify as transgender. We can talk about trans women without loss of generality. We know there exist men who have many feminine qualities of behaviour, who dress and present themselves in a manner that reflects this. There are also men for whom this experience of femininity is so profound that they feel literally like a woman trapped inside the body of a man. There are also men who do not behave like or look like women (except in the most transparently superficial way), men who may even have lived as a man for fifty years, who do not just call themselves women, but who are demanding to be known officially as women and to be able to use women’s public facilities. When designing policy, you must be sensitive to the full scope of this reality if you are to avoid aggravating social tensions. If there is one lesson we should draw from the 20th Century, it is that when governments simplify the reality too much, ignoring human psychology, they risk disastrous political consequences7.

Deep Freeze

“If we don’t believe in freedom of expression for people we despise, we don’t believe in it at all.”

Noam Chomsky.

Remarkably, there are still hyper-liberals who deny that there has been a “freezing out” of public debate on issues like transgender rights. This is strange because – before most people had had a chance to consider the transgender issue, or even learn what the debate was about – we were being told by friends and colleagues that the right opinion is self-evident and even to open your mouth in the spirit of debate is to kill, or potentially seriously harm, a transgender person. Often the response was so hysterical, so cataleptic, that it seemed better to remain silent on a topic so utterly remote to ordinary life.

I have found that hyper-liberals who deny that there has been any suppression of the discussion also believe, in no uncertain terms, that persons who disagree with woke policies should not be allowed to speak anywhere – online or in public. Unsurprising, then, that this might have had some effect on the debates. For years, Centrist intellectuals would skirt around the subject on radio and television, always speaking in generalities or using abstract terminology to avoid precipitating a backlash; academics and writers lost their jobs or felt compelled to leave8; and even famous transvestites and prominent scientists refused to discuss transgender people during recorded interviews9.

In defence of the damage done to the livelihoods and reputations of people during the course of the transgender debates, hyper-liberals often claim that these people couldn’t expect to voice their ideas without “opposition”, or that companies should be allowed to fire people with views that are “against their ethos”. But both of these arguments strike me as disingenuous. When someone is calmly and politely saying that they disagree, or they think that hyper-liberal policy proposals should be discussed, to scream that they are killing people and they should lose their job or be physically attacked is in no wise a proportionate reaction.

A Culture of Infinite Softness

“…explain that you wish merely to aim at making life simpler and harder instead of softer and more complex, and the Socialist Party will usually assume that you wish to revert to a ‘state of nature’ – meaning some stinking Paleolithic cave…”

George Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier – p.202.

The ultimate goal of woke is a culture of infinite softness, where life is easier for everyone – no matter how detestable they are – so long as they are woke. The results of this campaign to accommodate everyone are apparent in our universities and government institutions, our schools and supermarkets, where everything is monitored, regulated and infantilized. Though the woke campaign has received broad support from our administrative middle class, it is not the only way one might go about improving society – it is the image we arrive at when “better” is interpreted as “safer”. There are myriad other ways that have been suggested over the course of history to bring about progress. Fascism is the result when “better” is interpreted as “stronger” and modern Western liberalism is what followed when fascist forces were defeated in 1945.

When a liberal agenda is allowed to advance unchecked, the drive towards inclusivity eventuates in a climate of mediocrity and selfishness. We end up with absurdities like a monoglot Foreign Office10 and gravestones plastered with safety instructions (Figure 2). In a bid to keep everyone safe, there is a proliferation of rules inside government organizations that demoralizes workers and reduces the efficiency of the system. This makes it easy for Right-wing critics to declare that our institutions are intrinsically flawed, or the liberal mission at fault, when the reality is that the liberal vision has been extrapolated beyond reasonable bounds.

The pursuit of a softer society goes hand-in-hand with technological development. Gray has already explored the conflation of ethical and technological progress in hyper-liberal thought11. The cumulative advance of scientific knowledge is seen by many as proof that Western societies have become more rational. The hyper-liberal is therefore working towards a technological utopia where every problem is solved by a machine, everyone is safe and humans have complete freedom of choice. They do not think seriously about what this dream society would look like, or the types of people who could live in it. There is no reason to suppose that a decent human being can thrive in contemporary society – let alone a woke utopia – filled with screens, endless rules and procedures, near-perfect safety and robbed of the sounds and smells of nature. It is far more likely to cater to fearful, socially dysfunctional, mirthless technocrats, who obsess over their coffee, Formula 1 racing and slapstick comedy. You only have to look at current statistics on the mental health of young people to see how undesirable a techno-utopia would be.

Orwell saw the danger too. In The Road to Wigan Pier, he described how pursuit of progress via unending technological advance could produce a longing for Fascism:

“With their eyes glued to economic facts, [socialists] have proceeded on the assumption that man has no soul, and explicitly or implicitly they have set up the goal of a materialistic Utopia. As a result, Fascism has been able to play upon every instinct that revolts against hedonism and a cheap conception of ‘progress’… It is far worse than useless to write Fascism off as ‘mass sadism’, or some easy phrase of that kind. If you pretend that it is merely an aberration which will presently pass off of its own accord, you are dreaming a dream from which you will awake when someone coshes you with a rubber truncheon. The only possible course is to consider the Fascist case, grasp that there is something to be said for it, and then make it clear to the world that whatever good Fascism contains is also implicit in Socialism.”

And who wouldn’t yearn for some true grit and acceptance of personal responsibility when faced with certain members of our middle class – those who are too anxious to leave the house but think they know how to run the country? Who wouldn’t look back wistfully on a time where things were a little simpler, a little more honest and authoritarian, when politicians had a vision that could be clearly communicated and commonly subscribed to, so that we might set to work on it with gusto? The difficulty lies in convincing people that Fascism is not the answer to our problems with woke and neither is a kind of selfish hedonism. Change should come from the Centre and radiate outwards. Unfortunately – and in accordance with Hegel’s picture of society as a sweeping pendulum – policy is increasingly being dictated by Populists and authoritarians instead.

Implicit vs Explicit Understanding

“… It is the special illusion of literate societies that they are highly aware and individualistic.”

Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media – p.250.

Perhaps we are being failed by our exaggerated literacy. Most of us now live in societies that only value explicit understanding12. When we cannot write down what a woman is, we are driven into an apoplexy of confusion. In an effort to satisfy everyone, we become blinded by edge cases that do not fit our intuitive, implicit vision of womanhood. For hyper-liberals, it doesn’t matter that Richard Dawkins can supply us with precise scientific definitions of male and female13 because these definitions cannot satisfy everyone in society. The woke conclusion is that the definition of womanhood must be scrapped – that it is meaningless. Iain McGilchrist has this to say on the subject14:

“Once our lives become very largely mediated by self-reflexive language and discourse, as in our postmodern world they are, the explicit stands forward and the implicit retires. Yet almost everything that really matters to us – the beauty of nature, poetry, music, art, narrative, drama, myth, ritual, sex, love, a sense of the sacred – must remain implicit if we are not to destroy their nature.”

The Art of Woke

“… A lot of what we’re doing at the moment doesn’t seem like a culture that is intent on transmitting its values, practices – even artefacts and rituals – into the future. It feels like a culture with a great deal of anxiety about the future… And there’s a problem with the avant-garde… There is no avant-garde anymore. There’s just f*cking Starbucks. And there’s that headline in the Onion: ‘New Starbucks opened in restroom of existing Starbucks’. And that’s the contemporary avant-garde: it’s a Starbucks opened in the toilet of an existing f*cking Starbucks. And you know, a culture without an avant-garde is a culture with no tension; no creative tension between what the norm is – what good, solid family entertainment is – what people are allowed to say and what they aren’t allowed to say. In a way, the avant-garde destroyed itself. It was bowdlerized, it was commercialized and it shot itself in the foot through its own excesses, but nonetheless it’s one of the canaries in the coalmine that tells us we’re in deep doggy doos…”

Will Self. Transcript from “Will Self: A Life in Writing” at the Southbank Centre.

The postmodern obsession with explicit knowledge doesn’t just apply to the transgender debate – we are equally confused if we cannot prove there is a single, “right” way of thinking or cannot write down a general recipe for beauty. Perhaps this reflects the importance of technocrats to the economy and the loss of craft-based skills.

Walking around art galleries today, any criticism on grounds of quality of draughtmanship is seen as an artefact of privilege. Art must be accessible, which people interpret as meaning that any moron is good at it as long as they are making some cheap political point. The politicization of artistic appreciation is well illustrated by the rise and fall of Lizzo. I still recall the exclamations of shock when I said I didn’t like some of her music videos. The implication was that, if you weren’t a fan of her bluntly explicit rap music, or didn’t find this grotesquely overweight and spectacularly unsubtle person beautiful, then you were a chauvinist who could only appreciate conventional pop idols like Shakira or Katy Perry. After allegations of (ironically enough) weight-shaming and sexual harassment were broadcast, however, Lizzo’s celebrity endorsements evaporated and people mysteriously stopped listening to her music. With remarkable celerity, her fans assimilated the new “reality” that she was not a good singer after all. Now, it seems, the champion of beautiful obesity is fast losing weight and approaching the identikit Barbie figure the woke secretly crave. Like the rest of her fans who shout about body positivity and then flock to buy make-up and gym memberships, they do not really believe humans are all equal. It is impossible to think so.

Hyper-liberal tastes have extended their influence like a pall over many aspects of our cultural life, leaving them subdued by a kind of dreary censoriousness. Last year, when a friend played me a video of Zara Larsson’s “Midnight Sun”, I laughed at the incongruity of this woman singing at the summit of a Norwegian mountain wearing a sparkly tennis visor and a slit crop top, her thong riding up suggestively over tracksuit jogging trousers. The laughter was short-lived, however, as I was coldly informed that Zara might just be more “comfortable” in those clothes – even as we watched her push her trousers lower on her hips and caress her bust and her hair. Many hyper-liberals see it as essential to women’s liberation that women play no part in seduction – that women’s bodies be perceived as lifeless and undesirable. They see the male appreciation of female beauty in art as somehow unseemly, yet at the same time they are happy to watch the most obscene species of pornography provided the “action” is not directly harmful. While hyper-liberals sit with eyes ostentatiously averted, the rest of the world continues to employ exactly those techniques of erotic suggestion that they pretend don’t exist in advertisements, films and their own personal lives.

The Tone and the Music

“With much of it, Smiley might in other circumstances have agreed: it was the tone, rather than the music, which alienated him.”

J. LeCarré, Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy – p.388.

“… he would strike with the merciless venom of the fanatic for whom the world holds no gradations – only black and white.”

Mervyn Peake, Gormenghast – p.569 of the Vintage omnibus.

More important even than its philosophical shortcomings, it is the tone of hyper-liberal discourse that is damaging to the liberal project and to public debate in general. The extremity of the woke reaction to discussions of transgender rights led almost immediately to a freezing of debate on a range of issues. In both the public and private spheres, people with moderate views retired from conversations to avoid being misrepresented or misunderstood. Many politicians on the Centre and Left ceased to have personal opinions because they weren’t sure what views were considered permissible. Important writers (e.g. J. K. Rowling, Kate Clanchy), academics (e.g. Kathleen Stock) and political figures were “cancelled” – that is, either they were fired, had awards stripped from them, or were considered so morally compromised that they were written out of history.

In private, conversations with hyper-liberals started to feel like fording a frozen river. It was difficult to know what kind of reaction people were capable of. I myself have observed friends give vent to weird, vitriolic outbursts in the course of normal conversations, where they wish death and ruin on a particular writer or philosopher whose work they have not read and whose arguments they have wholly misunderstood. I have had discussions about trans rights and immigration where my red-faced interlocutor is practically shouting, where veins are pulsing like subcutaneous serpents in their temples, only for them to insist afterwards that the discussion was perfectly amicable – even “fun”. This problem of proportionality, of respectfulness and tone, is rarely observed when talking to people aligned more with the political Right. Though I may object to many of their ideas, Right-leaning people tend to lack the shivering neurosis of some hyper-liberals and the terrifying conviction that their opponents are evil. They do not start screaming that you are threatening someone if you disagree and the result is generally a lively, enjoyable discussion that both parties can learn from.

The tone you adopt in a conversation is the outward expression of your frame of mind. If you cannot speak to someone who disagrees with you without the conversation degenerating into a bitter argument then it is a poor advertisement of character. Respectfulness and politeness are particularly important in public discourse, where the goal is to educate and inform. A degree of trust is required from both parties – a willingness to believe that there is some truth in each other’s perspective. The difficulty is that hyper-liberals think that they are right by default.

There are few acts more pungent of dogmatism than telling someone they are not allowed to not take sides; that if you are not with the hyper-liberals, you are against them and if you are not sure whether you think a “trans” person should be formally recognised as a member of the opposite sex then you are transphobic. To say that if you do not believe them then you want to kill them is a form of hostage-taking. The same tactics were used in the Cold War with Soviet Communism and McCarthyism – and it is happening again today with woke.

The importance of tone, which is eloquent of character and one’s willingness to enter honestly and enquiringly into discussion, is addressed repeatedly in the novels of John LeCarré. LeCarré sketches the British liberal and Soviet communist approach to espionage from different angles. His heroes are flawed but admirable, combining a “feeling heart” with a “corrosive eye”. They are meant as a vindication of the age-old British trust in “character over intellect”15 – the belief that there are qualities more important in a leader than the horse-power their brain can convoke. There is knowledge buried in diverse places – and even first-rate minds can be betrayed by solipsism, through ignorance of the experience of others.

This is not to say that LeCarré presents the liberal side as uniformly good and the communist uniformly bad – his novels are shot through with criticisms of the liberal side and the ethical difficulties the spies are forced into – but he certainly paints the liberal characters as more conflicted than the communists. They are more self-aware, less fanatical and have a greater potential for compassion (even if, often, their methods are just as devious as those of their opponents). In the words of George Smiley – who is a kind of banner-bearer for the liberal cause – the British service should be16:

“…inhuman in defence of our humanity, harsh in defence of compassion. To be single-minded in defence of our disparity.”

LeCarré – through Smiley – is acknowledging the contradiction; in order to defend our liberal values, sometimes extreme methods must be used that could not otherwise be tolerated, from which one’s conscience recoils. This can be contrasted with the attitude of his Communist counterparts, who see their ethical principles as consistent, who have a fanatical loyalty to their regime and for whom ends always justify the means. For them, their ideal conception of a communist society has grown so large that it occludes the reality of the human condition. What they see as strength is in reality a fatal weakness17:

“All our work – yours and mine – is rooted in the theory that the whole is more important than the individual. That is why a Communist sees his secret service as a natural extension of his arm, and that is why in your own country intelligence is shrouded in a sort of pudeur anglaise.”

In the end, both sides in the Cold War were willing to do appalling things in order to get ahead in the game of intelligence, but the impression you have from LeCarré’s writing – whether or not it is true I cannot say – is that the British “owls” retained a degree of scepticism, perhaps even uncertainty, throughout. I consider that significant.

Orwell also felt that the state of mind in which you approach a necessary (though perhaps distasteful) thing is important. He writes in The Road to Wigan Pier18:

“The sensitive person’s hostility towards the machine is in some sense unrealistic, because of the obvious fact that the machine has come to stay. But as an attitude of mind there is a great deal to be said for it. The machine has got to be accepted, but it is probably better to accept it as one accepts a drug – that is, grudgingly and suspiciously. Like a drug, the machine is useful, dangerous and habit-forming. The oftener one surrenders to it the tighter its grip becomes.”

It is a persistent theme in the fiction of Orwell and LeCarré that humans are imperfect and our politics should reflect this. It is essential to understand that it is not defeatist to accept that humans are limited and that their needs are often in conflict with one another. There is no other way for a social, biological animal to be. It is for this reason that we embrace a degree of compromise, a degree of hypocrisy. Policy-making is a constant tension between idealism and pragmatism, between needs and desires, viewed murkily through an aberrated lens. When the context changes, so too – sometimes – does the ethical course of action. No moral system of ethics is consistent. A consistent ideology would entail the annihilation of humanity. The British parliament, with two main opposing parties, is one way to balance the interests of different social groups. But hyper-liberals do not see it this way. They are looking for an immortal victory.

Choosing the Turd

Whether we are discussing the selection of products in a supermarket or the range of programmes on Netflix, giving the people “what they want” is nowadays seen as vitally important. The value of increasing “representation” is not clear-cut, however. Too often, this kind of democratic appeal is used to justify the persistent appearance of the lowest grade of product (cultural or comestible) in the marketplace.

If a third of the evening news is devoted to football in a time of international political crisis, or if ten seconds is devoted to entomology, then the editor must answer for their decision. And the decision should not always be made entirely on the basis of what the editor expects people will like. That is not the point of news presented as a compilation of current affairs (at least, that is the chief advantage of a publicly-funded national news service like the BBC – private news services must ally themselves more closely to the tastes of their clientèle). Nor is it possible to say that people truly want what they claim to want. You cannot want the unknown or unexpected. And do I truly want the thing I cannot help but desire? Would the public really prefer the gaudy trinket, the salacious tidbit, the sugared sweetmeat over a quality product? Whichever answer you choose, it is essential to recognise that your choice is never value-free. And the suggestion -usually promulgated by business owners – that supermarkets merely follow the tastes of the consumer is both wrong and disingenuous. Desire can be curated. It is not so difficult to convince people to buy the products on offer. New products are often produced in consultation with supermarket brands that are expert in consumer manipulation. The hyper-liberals think that when they choose who they are, or what they want to buy (Fig. 3), there is a kind of purity in their decision – a loyalty to their true and immortal self that justifies their choice. And they believe that this freedom is a right instead of a privilege.

The question of personal choice is particularly important in the education of children. Before hyper-liberalism, children were generally recognized to be only partially formed as personalities. They were impressionable creatures for whom we want the best and who must therefore be given lessons in reality, who must undergo trials like exams and competitions to strengthen character because we know that total insulation from stress and danger is damaging if they are to grow to live wholesomely and happily in the world. The current obsession with “choice” feels like a maniac response to Peter Weir’s Dead Poets Society. Horrified by the picture of the pitiless father who insists his son study medicine instead of art, hyper-liberals have decided that children should be allowed to choose what they learn, what they eat, how they eat, what sex they are – and that their conviction is the fruit of some deep, immiscible personal identity.

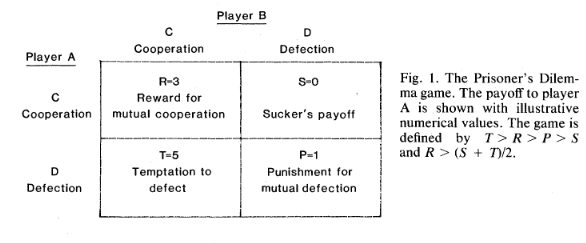

Should we play to the lowest impulses of the lowest common denominator to be “inclusive”, or do you provide children with content that pushes them, that feels excitingly adult? Looking at Fig. 1, I would suggest the answer is written plainly in the cards. When teaching literature at school, is it necessary for every (or indeed any) child to “understand” the entire text? Philip Pullman would say no. He would say that it is enough to feel the music of a poem and to understand it in part. A human is not a static quantity with an imperishable and inviolate soul – our personalities are constructed non-linearly as our bodies interact with their surroundings. We pick up lessons and fugitive images that recur in unlooked-for ways – both good and bad. Sometimes the value is only apparent later. In their effort to eliminate suffering for all children, hyper-liberals endanger the efficacy of the educational enterprise.

Free the nipple, free the soul

« Il faudra bientôt construire des cloîtres rigoureusement isolés, où ni les ondes ni les feuilles n’entreront, dans lesquels l’ignorance de toute politique sera préservée et cultivée. On y méprisera la vitesse, le nombre, les effets de masse, de surprise, de contraste et de répétitions, de nouveauté et de crédulité. C’est là qu’à certains jours, on ira, à travers les grilles, considérer quelques spécimens d’hommes libres. »

Paul Valéry, Fluctuations sur la liberté, 1938.

The imaginary human beings of woke thought are free. They feel they should be free to realise their desires, so long as they do not directly harm others. They feel that people should be free to make decisions about how to identify, how to behave, how to dress, how to think, because they can – because they possess, on some deep level, free will. The corollary is that people who do not behave as they should, or who do not believe the woke orthodoxy, are intrinsically evil. Orwell observed the same attitude in the Socialism of the 1930s:

“Faced by the fact that intelligent people are so often on the other side, the Socialist is apt to set it down to corrupt motives (conscious or unconscious)…”

Chap. 12.

Here, we have arrived at a vision of humanity that feels very Christian and a picture of the individual much like a soul. Indeed, this is precisely Gray’s conclusion in New Leviathans: that the woke movement has reinvented the Christian soul without the theological buttressing. They believe human identity is determined from the earliest stages of development, so children can be given tremendous freedom to make their own choices. Perhaps they see children as privy to a self-knowledge which adults gradually forget?

When postmodern society rejected religious explanations of how the world worked and came to be, certain ethical ideas, long associated with a religious outlook, also declined in popularity. We discarded the idea that humans should be modest and not challenge the gods, or that they would always be limited by the boundaries of the world and divine strictures, replacing them with an equally unscientific and hubristic humanist perspective, grounded in the idea that humans can be made “rational”, that we will transcend the boundaries of the Earth and that every problem has a technical solution because humans can do anything. It is from this new, human-centric position that certain members of the middle class feel able to declare that everyone is free and entitled to a VW campervan. Science repeatedly defies our expectations, but that doesn’t mean it can make subjective problems objective, or turn humans into gods.

Gray observes that the “freer” our liberal society has become, the more it must be “monitored and controlled”. This is because a woke Utopia is not just free, it is also safe, non-discriminatory and equal. Hyper-liberals do not see humans as animals except in the narrowest sense of us having evolved from primates. In their view, humans are perfectible and ethical problems have unique solutions. They do not see that total safety implies total control and total misery. For every additional freedom, a new rule must be made to enforce it. Kurt Vonnegut has already caricatured an equal society of this type in his short story Harrison Bergeron, where the “Handicapper General” dispenses handicaps to ensure that clever people cannot think too clearly, strong people cannot take advantage of their strength and beautiful people are made plain.

Politics is a closed surface. Go too far to the Left you end up on the Right. If you forget that humans are animals – inescapably limited, limited by definition – then you produce tyrannical systems of thought, like Soviet Communism and hyper-liberalism. Broadminded leadership is needed to maintain an implicit understanding of context, of human psychological complexity, if we are to prevent inhuman policies from being passed that presuppose infinite capacities of human organisation or flexibility of thought. The goals of equality and prosperity for all must be approached but never realised.

Reform – not Reform

Each age has its own political challenges and ours, it seems, is woke. If we are to make any further progress as a nation, we need to roll back the tyranny of the neurotic and return to a measured form of public discourse – where a disproportionate reaction is recognised as such. Various books and newspaper articles have recently been published asserting that woke is “dead”. And I grant you, in the eight months or so since I started this essay, there has been a selective thawing of the political landscape19. But the processes that drive political polarization have not yet disappeared. I notice the same hyper-liberal ideas cropping up daily in conversation – the obsession with personal identity, or the insistence that everyone submit to false choices between apparent opposites like being inclusive and exclusive, or strict and loving20. We must be wary of nihilism, free market consumerism and social isolation. Above all, on both the Left and the Right, we must avoid a politics of selfishness. When the self is sovereign over society, fear and self-preservation triumph over transcendent goals. We see it when people use poor government services as an excuse to avoid taxation; or when they claim that life ought not be difficult and people do not need to earn the benefits they expect from society.

When ideas like these become dominant across the political landscape, it suggests the liberal narrative has overreached itself. But this is not a calamitous, final repudiation of liberal ideas. Nor does it prove that they are unusually flawed. History is a record of the rise and decay of human institutions. Already in the last century, liberal institutions have cycled through periods of waxing and waning influence. If our conception of a good, liberal philosophy has stagnated and started to rot, the infected areas should be cut off, preserving those aspects of the original vision that are still beneficial in the context of the present age. A new movement can then be painstakingly rebuilt on the excarnated bones of the old. Jared Diamond has shown how, when countries are faced with existential crises, this type of selective rebirth is possible – in Finland, Germany and Japan, for example21. And Mark Carney has described how political pragmatism will be crucial for countries like Canada and the UK as they try to retain influence in a world dominated by superpowers that no longer pay lip service to common laws22.

Those of us who bemoan the current state of the political centre would do well to think about how this type of long-term strategy might be applied in our own approach to politics. I think it is less a question of being “smarter” (which many on the left associate with a lack of integrity) than of not being stupid. The problem is clear from the Left’s reaction to Keir Starmer, which has been consistently negative from the outset of his premiership. Just weeks after Parliament’s summer recess in 2024, left-liberal friends were complaining that Starmer hadn’t achieved enough, as though they expected him to magic up tangible change in one month, after fifteen years of austerity and Conservative rule. Starmer has since made progress on diverse fronts – with increased protection for renters, some improvements to rail services23, the economy, international relations and the environment24 – but his approval amongst Labour voters has remained low. There are various legitimate criticisms one could make against Starmer – his lack of conviction, his spineless initial stance during the transgender debates, his policies on the right to protest – and clearly there is a problem with Starmer’s own style of communication, which makes him appear curiously thin and platitudinous. But the real reputational damage amongst the middle class hasn’t come from what Starmer has done – it came from what he didn’t say, or wasn’t deemed to say quickly enough, as part of Labour’s response to the war in Palestine (which was essentially cautious, following persistent allegations of anti-semitism under Corbyn). The problem is not that hyper-liberals disagree with Starmer’s policies or rhetoric, it is that they allow a minor action on a single issue to colour their entire perception of him as a person. They do not suppose that Prime Ministers may have important (and necessarily obscure) reasons for acting in the ways that they do. This sort of “cancellation” is the ultimate repudiation of someone’s record, a kind of monstrously inaccurate extrapolation. It smacks of the same dogmatic pedantry seen in the wars of religion (which is what gave birth to liberalism in the first place).

I think one of the reasons people come up with absurd caricatures of politicians is they have no feel for who they are as people, or what their basic ethical assumptions are. If you have a realistic understanding of how politicians think, it is harder to be convinced by their portrayal in the media as fairytale villains. A podcast or radio programme might be used to address this. There could be interviews on basic moral questions, like in Radio 4’s Moral Maze, and there could be provision for politicians to talk more expansively about their dreams, helping us to separate out those with ideas – with vision – from those who do not.